Eddington

looking at Aster's new film and his cinema of punishment and transfiguration

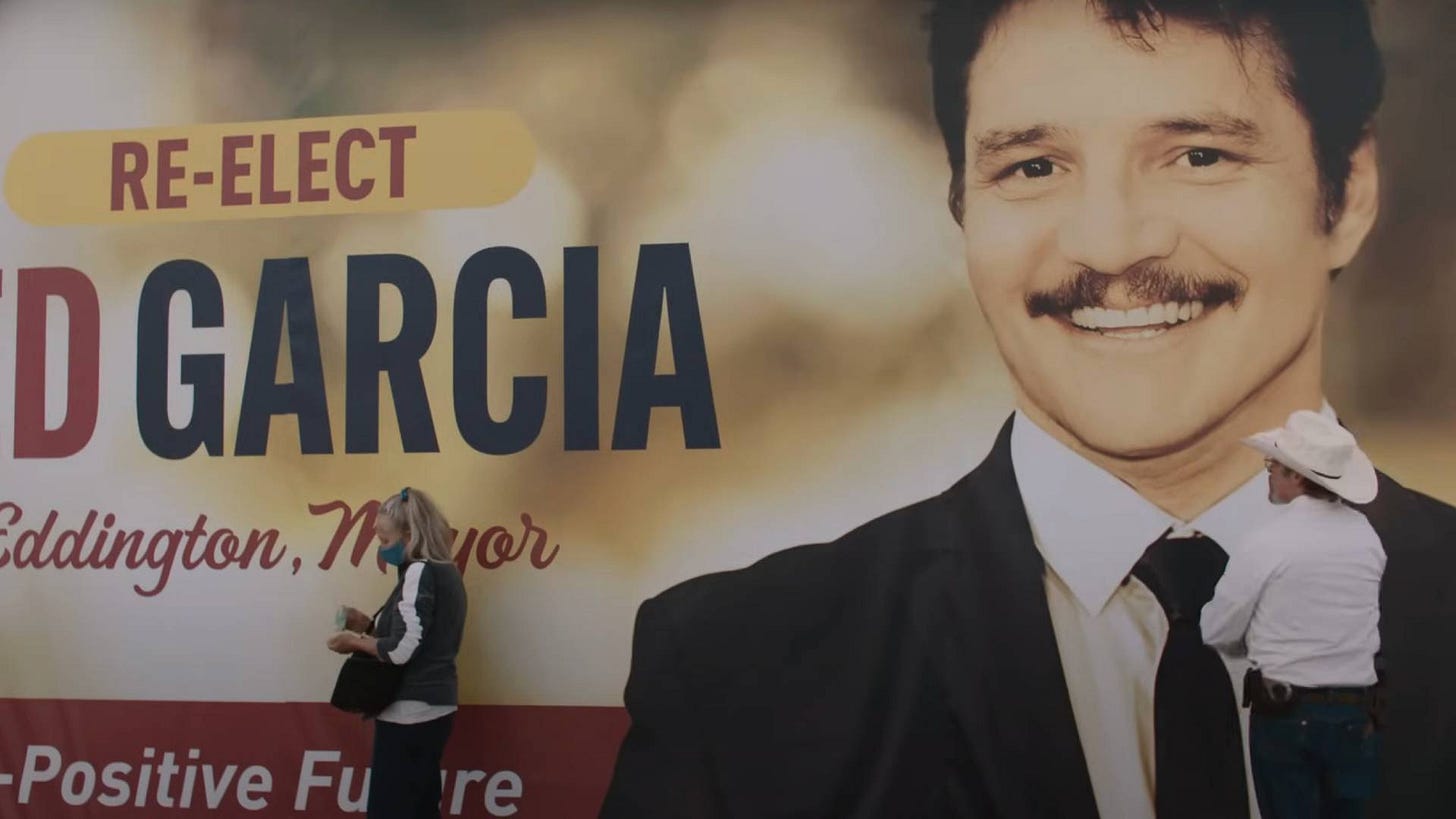

Remember this shot. As an unhoused vagabond trudges along a paved road, he mumbles to himself, clutching a dead bird. Inching along, he passes a sign for a multi-billion dollar “Data Center”. This is one of many dissonant images director Ari Aster gives us in Eddington, his sprawling diorama about the fracturing of American culture during the Covid-19 crisis in 2020. The film falls easily into discussions of "polarization" in terms of parsing Aster's (often contradictory) representations of right / left (or perhaps "left") schisms across battlegrounds like masking or George Floyd's murder. But a lot of these discussions miss the film's most glaring moral indictments. While, yes, Eddington expresses the chaos fueled by the increasingly aestheticized political environment that finds its accelerant on the internet, it also suggests that this chaos ignores both America’s "macro" and "micro" extremes of political consequence. For instance, on one end of the spectrum you have the aforementioned massive Data Center slated for construction on the edge of town. This Data Center is positioned as harbinger of massive sociological and environmental change, despite its sunny framing by the Tech Oligarchs constructing it. No matter how fervent or violent the depictions of America's micro-ideologies become, those looming environmental or sociological implications for the citizens of Eddington are rarely addressed except for in the vein of conspiratorial thought and thus their significance becomes more muddled. More importantly, those financial interests responsible for the construction of the data center operate in the film's background fabric (here represented by the enigmatic Warren Sandoval who is untouched by the town's splintering factions but a clear orchestrating backer of liberal minded Mayor Ted Garcia’s re-election campaign. At the other end of the spectrum, a seemingly schizo-affected homeless man whose continuous pleas for rescue from his suffering also orbits the periphery of the film and is overlooked by most of the town, including even the "progressive" minded youth. In the opening shot of Eddington, Aster brings these two ends of the spectrum together in dissonant harmony.

Eddington centers primarily around Sheriff Joe Cross, an anti-masker (he claims his asthma makes it difficult to breathe) who lives with his neurotic wife Louise and her conspiracy, brain rot addicted mother, Dawn. Sheriff Joe’s anti-masking activism has a seemingly sympathetic bent to it (at first) as he outlines how it degrades social bonds and creates fraught relationships between the citizenry and their government (a particular scene shows a hapless customer being physically removed from a department store). But this facade of the “altruist anti-masker” is soon dropped, when, finding himself at his limit, Sheriff Joe Cross mounts a Conservative Mayoral challenge to the previously unopposed Ted Garcia. As the picture unfolds, it becomes clear the “anti-masking” philosophy of Joe Cross and the auspices of social community he upholds, merely papers over his reactionary sympathies and his internet fixation provides a pipeline to fulfill his fascist down-spiral.

Parsing which characters are more "captive" to the quick drip of online invective becomes difficult because it is apparent that they're all hooked - not only are they hooked but this onslaught of material is an inexorable part of the characters’ communicative faculty. This is most readily seen in Dawn, but every character from the black lives matter teenagers to Sheriff Joe himself, are reduced to a series of inputs and outputs. Sheriff Joe’s Mayoral Campaign is not singularly an output of his impotence or frustration with laws he perceives as draconian but he has consumed so much “content”, he must manufacture content himself (his candidacy). In Aster’s mind, we are all being reduced to two-way valves for content. Nobody is processing but everyone is consuming and regurgitating. Additionally, the BLM teens in this film, source of much comedy, aren’t perceived as ridiculous because they recite catch-phrases and abstract critical theory in a way that is borderline inapplicable in a tiny south western community, but rather, they lose sympathy because none of it forms a tangible framework to deconstruct their society and its looming malevolent structural changes and glaring social inequalities. It atomizes and isolates but it does not clarify (if anything it obfuscates).

One could (and many have) charge the film as “centrist’, but this is, in my opinion, a meaningless term for a film like Eddington. Despite Aster leaning into his puckish instincts which often manifest in some reactionary through lines for some counter-valence, it becomes clear he views Sheriff Joe’s “moderate conservatism” as the more pernicious element. Upon his wife’s departure to live with a new-wave cult, he finds the homeless man breaking into a tavern (the town’s only visible down and out). The desperate man tragically expresses his dire circumstances “You don’t care about me / you poison me, i’ll poison you”. Here we have an expression of his material reality and his relationship to the world around him and in response our fast on the “Bickle track” Sheriff shoots him dead. Aster might engage in the presentation of a balancing act in part to give Eddington texture but there is an ideology that he views socially and immorally destructive as opposed to one that is mis-engaged.

However, Sheriff Joe’s emasculation doesn’t begin with the threat of divorce. Early in the film we see a nearly intimate scene with Louise interrupted by her anxieties. Sheriff Joe, feeling frustrated sexually (despite expressing sympathy to his wife) turns over to scroll more mindless content on his phone, the first indication that his reactionary tendencies are related to his feelings of impotence. Another source of impotence is the image of Louise’s deceased father hangs large over the Cross family (quite literally), whose own legacy as a former Sheriff casts a shadow over Joe Cross’ endeavors. Now we need to understand a bit of Aster’s formal lexicon. When we first see the shrine, in the form of a large portrait ordained with candles, it is framed in stagey, artificial symmetry (like a diorama). During this sequence (which happens at breakfast) the Cross family orbits this shrine centered in the middle of their home, positioning themselves around it as if it were the center of the universe. Aster often builds this sense of artifice to signal an ominous or foreboding presence (something here compounded with Aster’s demonstrated fascination with malevolent family secrets). Eddington never totally confirms the suspicions initiated by this shot, but Louise’s neuroticism and her mother’s obsession with Ted Garcia (who she believes violated her daughter) come to a rather telling climax when Sheriff Joe Cross is ambushed by Louise, Dawn and Cult leader, Vernon Jefferson Peak, at dinner. Vernon proselytizes to Joe, telling him of his abuse as a child and importantly that “love and evil” can co-exist. This causes a fissure between Louise and Dawn, the latter excuses herself, muttering deflections. At night, Joe repeats the raised suspicions to his wife asking her “did your father ever…” before bailing and pivoting to his nemesis, blaming Mayor Ted Garcia. Much in the way conspiracy theory deflects from the source of material inequities, it also diverts the characters ability to engage with their own traumatic condition. Instead of trying to connect with his wife, Cross arms himself with this conspiracy, falsely accusing Ted Garcia and commits himself to becoming the embodiment of reactionary political violence. This culminates in Cross shooting the homeless man, and murdering his political opponent and his teenage son. Critics have painted this film as intending to depict warring equivalent spheres in the COVID scrum and yet there is no arguable counter-valence to Cross’s murder spree. It is as cruel an action as committed in the picture and presented without equal.

As all this unfolds, there is a formal dissonance between the digital screens the sprawling Western backdrop. While many filmmakers struggle to intertwine their film's milieu with the digital plane, Aster's freewheeling employment of it only demonstrates how alien it is. All the phones, laptops and digital interfaces are like a foreign body to the expanse of the desert or dirty store fronts. Similarly, the "archaic" auspices of a southwest town provides a perfect utility to underline there is no frontier that hasn’t been infiltrated. Contemporary small towns are often dissonant entities themselves, located adrift from financial capitals they bring civilization to nature. They are both physically isolated from the world’s greater mechanisms, yet, thanks to the internet, are as connected to the information infrastructure as a busy corner in Brooklyn. Yet in America, it is in these small towns where lies the nexus of capitalism’s many ills from fentanyl overdoses, environmental decay to job shortages all of which provide the conditions to satisfy the needed supply of disaffected boots to staff our overseas imperialist projects. Small towns form a barometer for the pulse of the country’s economic health, or here, a useful staging ground for Aster’s modern American parable.

If there is a unifying thematic idea across Aster's filmography (besides the nuclear family as a conduit for evil) it is likely the idea of punishment. Aster's characters are outcroppings of his neurosis, given flesh and pathos and castigated by him mercilessly on the screen. Yet, this is often deliberately contradicted by Aster also having feelings of transcendence running in tandem of his films concluding stanzas. At the end of Hereditary, Peter’s ascendancy as the satanic vessel, Paimon, is characterized by both the loss of his autonomy. the death of his family, but also the liberation from his guilt over the tragic death of his sister (for which he is partially responsible). Similarly, in Midsommar, Dani, experiences a transfiguration into the May Queen which is motivated by the sacrifice of her neglectful boyfriend but also liberation from her survivor’s guilt. Both characters, in abandoning their own flesh, existential and physical find an acquiesce to a new family, a reward for accepting the “punishment” thrust upon them. These sequences both share similar formal sensibilities depicted in a montage utilizing the Kuleshov Effect, framed with symmetry, while a score that feels simultaneously hellish and angelic builds to a crescendo that underscores the sequence’s fraught thematic through-lines.

With Beau is Afraid, however, (at release his most uneven, confused, but ambitious film) he casts aside this complicated and fraught dynamic for something more straightforward, putting Beau after his nightmarish picaresque journey on trial for his sins in a scene that evokes Pink Floyd's The Wall (at which point he is executed by drowning). Beau’s plight is one that is inevitable, it begins with a crime of neglect against his mother and yet at each “station” of Beau’s “passion” he finds his neurosis leads him to further inadvertent transgressions. The chaos around Beau is less a consequence of him pursuing selfish actions but rather a consequence of his internal malevolence being externalized - all his anxiety and diffidence bends the world around him and becomes a projection of his internal strife, making each stop on his journey more cruel and more corrupted. After an early screening of "Beau is Afraid", in a telling conversation with Scorsese, the old auteur remarked with horror something to the effect that "Beau didn’t deserve any of that". Aster, with some nervousness, impishly made clear he disagreed. To him, Beau’s sentence was unambiguously deserved. There is no transfiguration awaiting Beau, Beau is the character Aster has deemed the most sinful, which is why he is condemned to death with no redemptive transition. Aster as a filmmaker has typically employed his form to build “representations” (again perhaps to recall the word diorama). Think of him like the mother in Hereditary, building malevolent little dollhouses. It’s no shock Beau has the most overtly constructed artifice and theatricality in its staging and at times a cartoonish “brightness” to the colors. It is Aster’s vision of his own purgatory and eventual judgment, splashed against the screen like icons on a church wall. Beau is Afraid does not exist within split worlds like Aster’s first two horror features, but rather begins and ends his journey in total imprisonment by artifice. It should be noted this is the only Aster feature without an end credit needle drop, Aster here instead, opts for silence.

Understanding Aster’s films through this context might give us a framework through which to view Eddington’s most bizarre choice. Toward the end of the film as tensions mount, Aster takes the “antifa super-soldier conspiracy” and gives it a tangible basis in the film’s reality. The arrival of the soldiers (by way of a private jet) quickly sets off a mini-war as they directly engage Eddington's fascist Sheriff Department. While seemingly politically confused, Aster, is in effect, subjecting Eddington to a form of “punishment” and “retribution” in order to cleanse its reactionaries in a fire of “liberal violence”. Aster introduces them to the film’s chaos through the BLM “Black Square”, perhaps no clearer representation of toothless liberal political performance, one now largely lampooned for its total material ineffectiveness. But by repurposing its image (through a fading match cut) this harmless symbol of liberal token messaging feels like a summoning beacon for the Antifa Super Soldier Army. The iconography is appropriated and repurposed to corrective political violence within the film.

The tiny town cracks open in a hail of gun fire as our Sheriff Joe Cross makes his last stand. Vanishing briefly into a gun store, the doors fling open and he exits armed to the nines with military style hardware to do battle with the Antifa Knights. But despite being a clear “war come home moment” there is another revealing joke here. Isn’t this what we want to happen? Don't we want all this posting and aesthetics to result in clearing away all this fascist sickness? Aster in a moment that should be read with some sincerity (think Tarantino's Inglorious Basterds killing Hitler) gives us this violent cinematic catharsis (for a moment) culminating in Sheriff Joe being stabbed in the head with a knife.

The idea of “transfiguration” returns here in the films conclusion, though this feels like a sick inverse of Aster's previously more complicated renderings of that theme, combined with the unambiguous condemnation of Beau is Afraid and its concluding passage. Sheriff Joe, severely cognitively impaired as the result of the stabbing, now finds himself a drooling, wheel chair bound semi-conscious vegetable. Aster instigates this transfiguration through a POV shot following the stabbing, where Sheriff Joe balances between life and dead in a precarious state of limbo he must pass through to become Brain-Dead Mayor Joe. Aster, of course, ever the mischievous provocateur, seems to also be suggesting what he perceives as our own subconscious alignment with Joe’s maladjustment, and thus, capacity for for brain rot induced fascist backslide.

Winning the election by default and now puppeteered by both his conspiracy addled mother in law and the Tech Oligarchs stand-in, Warren Sandoval, Mayor Joe oversees the construction of the new Data Center and Dawn uses his platform to peddle her conspiracy theories. Intentional or not, this further hollowing out of the town and surrendering it to large corporate infrastructure under the guidance of a mentally absent overseer, is eerily reminiscent of Former President Joe Biden's Presidency. The fact that Sheriff Joe, like Biden, was a “Former” reactionary who found themselves the guardian of a late Neo-Liberal project only compounds the comparison. It must also be said there is simultaneously a Trumpian aspect to how conspiracy theory is utilized as the ideological structure that reinforces corporate oligarchy.

In the final moments of the film Mayor Joe's slack-jawed face, smeared with a vacant expression, watches the John Ford picture Young Mr. Lincoln. Ford, largely known among cineastes for his contradictory explorations of America, often has quotidian American pageantry run up against the most vile and pernicious aspects of its genocidal frontier project. But his biopic of Lincoln should be noted for being his most hagiographic depiction of American values, portraying Lincoln as a magnanimous mythic hero who embodies them. Mayor Joe, a corporate vessel, basks in the silver light of the picture’s stark contradiction to his own political image, living mentally absent in the haze of idealized American mythos. Once again its inevitable to think of Joe Biden and Donald Trump’s Presidencies, which both encouraged the incoming apocalypse of student debt, the consolidation of Tech Empire and the genocidal project in Gaza as they cognitively wilted in their twilight years, each cocooning themselves in the illusion of their own legacy. As America accelerates through its late-empire phase, tumbling from one mentally impaired manager to the next, Biden and Trump serve as a demented fun-house mirror to the country’s condition while our oligarchs lean more and more on our formative mythology as a shroud to disguise the rot that eats away at this country’s infrastructure, the soul and moral compass of its citizens and, quite literally, the brains of its bureaucracy. Eddington may not address all these ills directly, but it understands the types of Neo-Liberal custodians that would be produced by COVID-era activism.

The credits are rolling. Here Aster leaves us with one more dissonant image: the town of Eddington, shot from a bird's eye view, clashing against a vast western canvas, balanced in frame by a larger twin, the even brighter, sleek modernism of the expansive data center. While Eddington builds its parable in recent history, its final image tilts toward our future.

You have creative insight into Aster's cinema, but I can't help but find characters becoming disabled as punishment as a genuinely regressive trope he consistently uses. Such representations are degrading beyond the impaired characters and further trouble our real-life relationships with and understanding of disabled people. Symbolizing Joe's disability as a political/ mental absence/incognizance and as a parallel to the very intentional imperialist and extractive violence of abled American presidents is a degrading interpretation. Aster manufacturing disability in his characters as negative symbols of punishment, futility, weakness offers us distorted meaning to interpret in his work that critics should be cognizant of before weaving it securely into their critique.